International Perspectives – Dark patterns online – and the role of parents

Written by Dr Claire Bessant and Dr L. Lin Ong

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Laurel Aynne Cook, Mariea Grubbs Hoy, Beatriz Pereira, Emma Nottingham and Alexa Fox, who collaborated with the authors on the design of this study.

Has your child ever signed up to a ‘free trial’ for you to later find that they (or you) have been charged for a subscription? Have they been manipulated into sharing their own or their friends’ personal information as a condition of playing a game or using a service? The online sphere is full of these ‘sneaky tricks’, often alternatively referred to as ‘dark patterns’, deceptive patterns, deceptive design, persuasive design, harmful design and nudge techniques. Such dark patterns are designed to manipulate individuals (adults as well as children) into doing things they don’t mean to, like buying or signing up for things.

Children’s greater vulnerability to online harms is explicitly recognised in the US by the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) and in the UK by the UK General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Online Safety Act 2023. In both countries, parents play a key role as gatekeepers, protecting children’s online privacy when young children wish to engage with the online sphere. However, little is known about parents understanding of how dark patterns impact on children or about the actions parents take to address the potential harms dark patterns pose. In our research, we asked parents in the United Kingdom and in the United States whether they were aware of their children’s exposure to dark patterns, whether they believe it is their responsibility to protect their children from dark patterns, and if so, what steps they take to protect their children from dark design.

Dark patterns

Numerous organisations across the globe, including the OECD, the European Data Protection Board, Australia’s Consumer Policy Research Centre, CNIL (the French Data Protection Regulator), the UK Competition and Markets Authority and the US Federal Trade Commission recognise the negative impact of dark patterns upon (adult) consumers’ autonomy, privacy, finances and their emotional and social wellbeing. That dark patterns pose specific issues for children is also acknowledged by regulators in both the US and the UK. In the United States in 2022, the Federal Trade Commission took action against Epic Games (for ‘tricking’ children into paying unwanted charges). In 2023, over 30 US states brought a combined lawsuit challenging Meta for using manipulative design features to induce children into compulsive, lengthy use of platforms such as Instagram. The UK Information Commissioner in its Age Appropriate Design Code explicitly cautions online app and website designers against using nudge techniques which may ‘lead children to make poor privacy decisions.’

Parents’ responsibility for their children’s online experiences

Parents are often viewed as ‘the primary wave of defense to protect children from modern media.’ They are in the uncomfortable position of being both required to provide children with access to technology and responsible for protecting them from the risks it poses. However, many parents did not grow up with the internet, and lack the knowledge and skills needed to support children’s safe use of online technologies. It has been suggested that where digital businesses engage in exploitative behaviours ‘parents are likely to be overwhelmed’. Given such expressed concerns, which suggest that parents’ may be unable to effectively protect children from deceptive online design, our study sought to explore whether US and UK parents are aware of the risks posed to their children by dark patterns, whether they take actions to minimise or limit the impact of dark patterns upon their children, and who parents believe should be ‘responsible’ for addressing the dark patterns their children encounter.

How do parents protect their children online?

Using an online survey, we showed 185 US and 290 UK parents/caregivers multiple examples of dark patterns that might be experienced by their children and then asked them what actions they take to minimize or limit the impact of online design upon their children. Overall, US and UK parents provided similar answers to this question, with approximately ¾ of US and UK parents noting that they restrict access to apps/sites and do not link a credit card to children’s devices.

When presented with a list of online support mechanisms or tools and asked which of these options they would find most useful to support their digital parenting, evidence of a divergence between parents in the two countries then became evident. We list the top five most helpful ideas for both the US and UK, which surprisingly have little overlap.

We would suggest that these differences can perhaps be best explained by the different views that these UK and US parents held about who bears responsibility for protecting children in the online sphere, which we explore further.

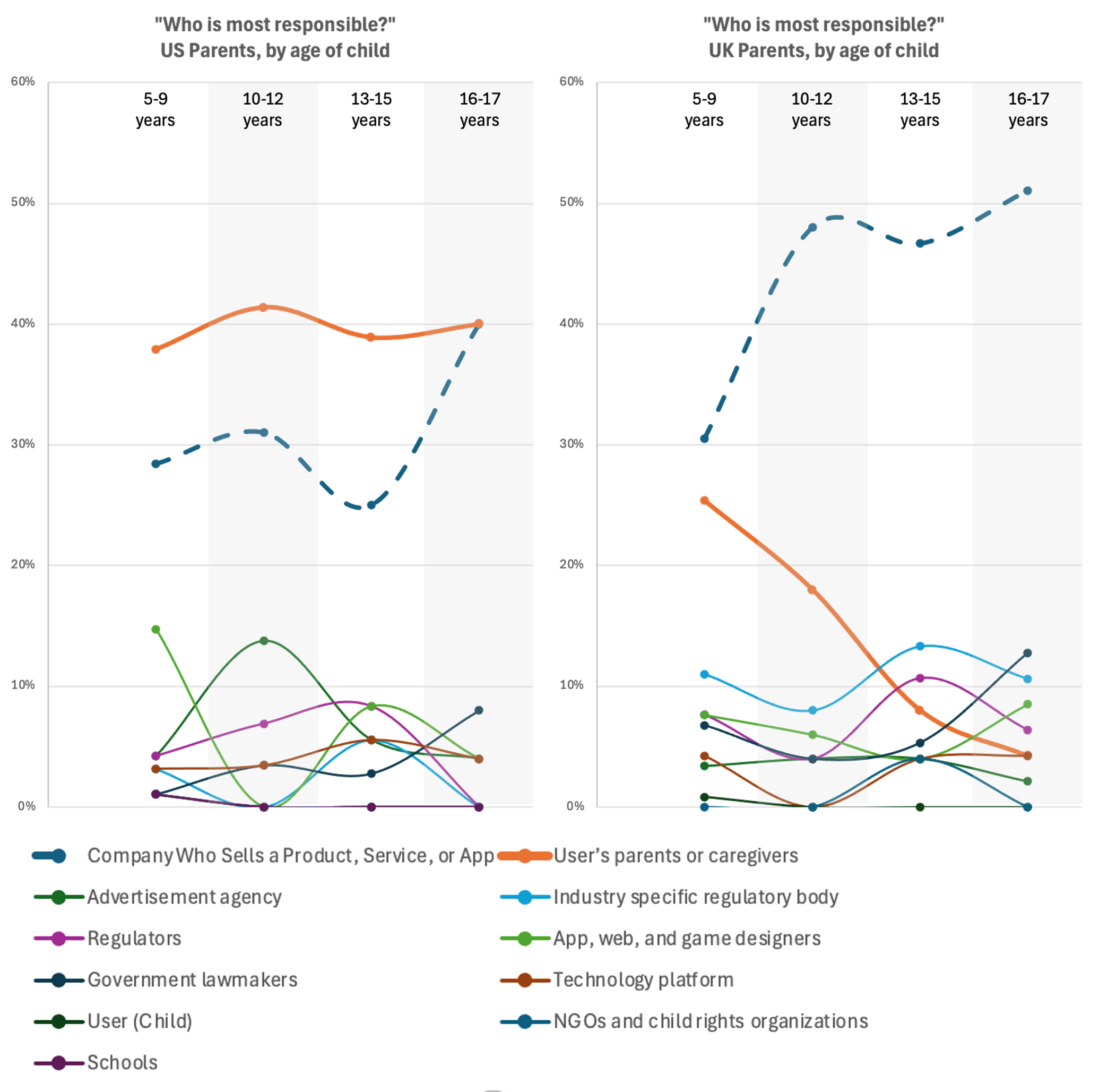

We then asked parents “who is the most responsible for addressing online design seen by children?” and required them to select one response from a list of options. Overall, US and UK parents suggest that the two parties most responsible are (1) a child’s parent or caregiver and (2) the company who sells a product or service. UK parents, however, put more focus on the company, while US parents believe caregivers are more responsible. In both countries, parents place far less responsibility upon platforms, app, web and game designers, legislators, regulatory bodies, and schools.

To account for parenting differences depending on the child’s developmental stage, we looked at responses by age of child. Strikingly, the US parents considered themselves to have the primary responsibility for addressing dark patterns; this was consistent regardless of their child’s age, although they also thought that the company’s responsibility also increased as the child grows older. For UK parents, a very different picture is evident; UK parents view the company who sells a product, service or app as primarily responsible for addressing online design. For the UK parents, the companies’ obligation to address the risks posed by online design increases as their child ages, whilst the parents’ responsibilities decrease.

Policy implications

This preliminary exploration into parents/caretakers’ understanding of dark patterns provides critical context for policymakers tasked with responding to an increasingly commercialised online environment, which makes extensive use of dark patterns to influence the online behaviours of adults and children.

We should not be surprised that both UK and US parents perceive that they have some responsibility for addressing the risks posed to their children by dark patterns. Such an emphasis is evident in legislation and policy in both countries. Similarly, it is not entirely surprising that parents believe that companies also have a key role to play in this regard, especially given the 2023 enactment of the UK’s Online Safety Act. Nonetheless, as our research illustrates, US and UK parents have different expectations, and place a different emphasis on the relative responsibilities of parents, companies, regulators and educators. These are important differences which we argue that policymakers should consider.

The Digital Child suggests in its Manifesto for a Better Children’s Internet that ‘successful regulation requires a fair balance between government regulation, technology company policies, and personal responsibility’. Where exactly that balance lies is not made explicit and, our research suggests, is likely to vary by country. The Manifesto argues for a ‘better Children’s Internet’ that ‘puts less emphasis on individual practices and fairly distributes responsibility of safety across all stakeholders.’ Whilst we would not disagree, we would argue that where the user is a child consideration needs also to be given explicitly to the parental role. Our study suggests further that the age of the children concerned and the culture/laws in the country where that child is living must be considered and will potentially influence parental views about where responsibility lies.

Looking for more content?

Our researchers and partners produce regular blog posts and research outputs focused on children and digital technology.